Lacquerware and Japan are so interconnected in our western minds that in some countries and periods “japan” “japaning” were (are) words used for lacquer works. Same as china for porcelain. But in reality – most of us don’t know about urushi, not to mentions it’s different styles and where they come from. Today in Japan there are over 20 regions and often distinct styles of lacquerware craft. Some of you have heard of Wajima or Echizen but there are many more of them. Below I list all I was able to identify, and describe some of them, not necessarily most important or well known, but just interesting 😉

Aomori prefecture

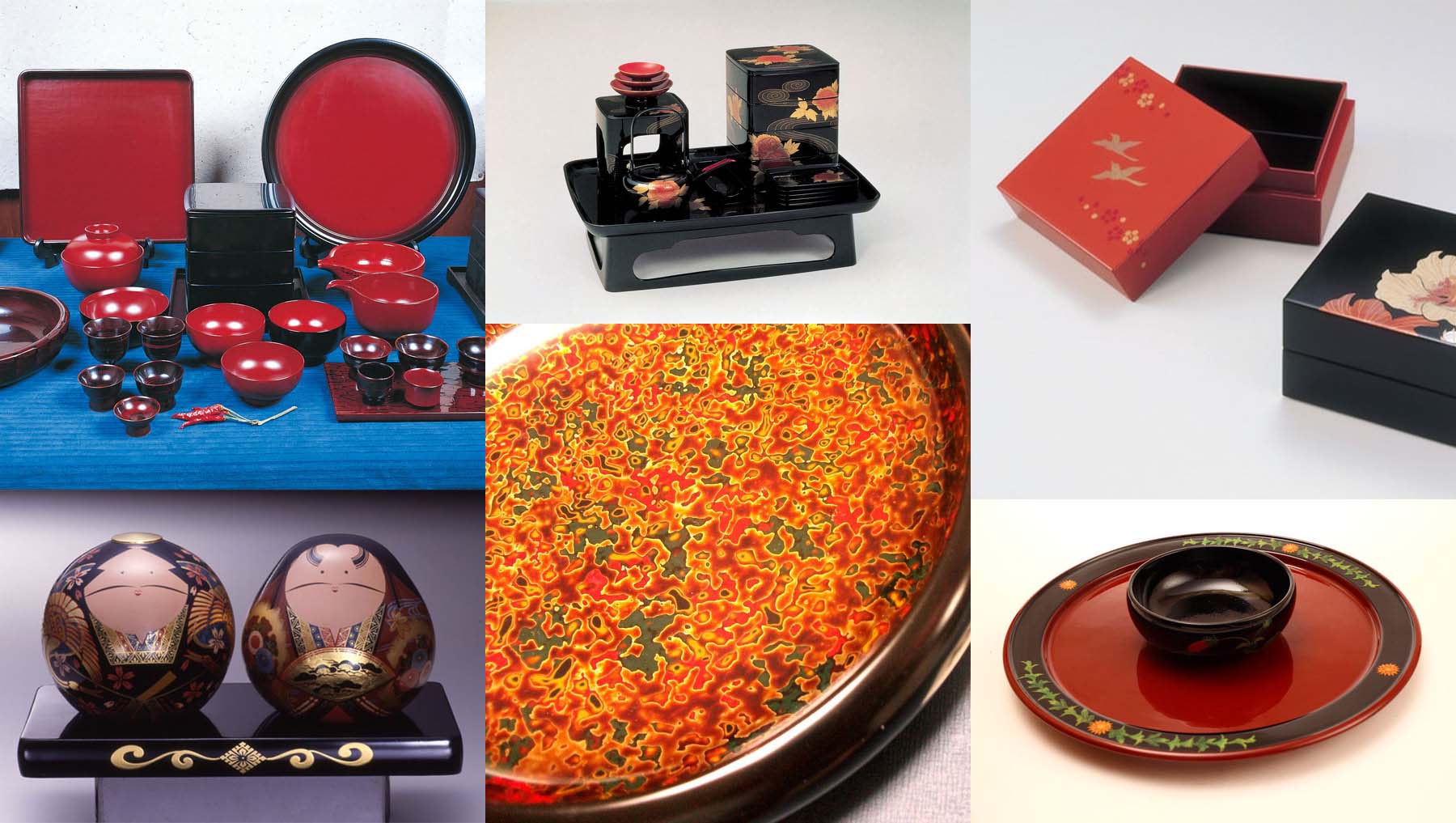

Tsugaru-nuri was produced in the region since Edo period (17th century) but is called Tsugaru since World Exhibition in Vienna in 1873. Most lacquerware from this region is in togidashi kawari nuri techniques – multilayered patterns. Some of them are to some extent defined and most notable are: kara-nuri, nanako-nuri, monsha-nuri and their combinatio – nishiki-nuri.

Akita prefecture

Kawatsura-shikki is a region with a very long tradition of lacquer use. Localy developed technique of priming and base work with use of charcoal powder and persimmon juice (both cheap ingredients) allows production of cheap but durable lacquerware. Today over 60% of production are bowl, but other various products are made too – from furniture to small artistic items. One of nuritate techniques – hananuri originates in Akita prefecture.

Fukui prefecture

Echizen-shikki provides 80% supply for the domestic food industry and business. Mass produced, decent quality and extremely various lacquerware came from Echizen for hundreds of years. The region used to be also the biggest urushi harvesting area. Now most leisure used here comes from China. Echizen-shikki is very varied nowadays – from mass-produced, cheap, utility products to high-end objects with artistic value.

Wakasa-nuri – biggest chopsticks source on Japanese market (80%)

Fukushima prefecture

Aizu-nuri. Most important techniques: tetsusabinuri (cast metal looks), kinmushikuinuri with patterns made with rise chaff. For decoration – hira maki-e with use if keshifun (finest gold powder)

Gifu prefecture

Hida-shunkei is known for its deep colour of lacquer and unusual and sacred method of processing.

Ishikawa prefecture

Kanazawa-shikki is known for its gold leaf craftsmen, whose products are well known not only in Japan, and favored by gilders and maki-e artists. Lacquerware from Kanazawa are often gilded, or decorated with maki-e. Many maki-e styles we know today are said to origin from Kanazawa. Substrate used is wood. Interesting process used in Kanazawa is wood hardening through soaking it in a mixture of diluted urushi and other resins, before any other steps are performed. Otherwise the process used in Kanazawa is very similar to Wajima.

Wajima-nuri – lacquerware from the city of Wajima is known not just for its finish, but mostly for the invisible at first aspect of quality – durability. Substrate is wood, and sometimes over 100 stages of production are needed to finish the product. In Wajima, urushi masters perfected the process of preparing the wooden base for next lacquering stages – preparing the wood, reinforcing the joints, strengthening the surface. Unique quality of jinoko (powdered diatomaceous soil) used for base work, found only in Wajima is one of the factors which sets Wajima-nuri appart, probably second only to Kyo-shikki which is as durable but also more refined.. Historically, sheer durability of Wajima-nuri was the most important factor for choosing lacquerware from this region, mostly as sturdy household items. Its more artistic connotations are relatively fresh, and started to bloom after 1975. Typical colours are black and red (shu, vermilion). Decoration is typically chinkin and hira-maki-e.

Yamanaka-shikki – one of first areas to adopt “modern lacquerware” substituting wood with plastic, and urushi with urethane lacquers. Today both – traditional wooden products, and modern plastic ones are made. Process used is similar to those of Wajima and Kanzawa, but with many products made with fuki-urushi and other techniques exposing wood-grain, often later decorated with maki-e. Traditional colours are shades of red and brown (bengara), but also black and recently much more colours.

Iwate prefecture

Joboji-nuri – an interesting region, as unlike in other mostly locally harvested urushi is used, characterized with unusually high urushiol content even in raw lacquer. Joboji area is also the biggest producer of lacquer in Japan – provides over 60% of all Japanese urushi for the domestic market. Most important restoration works in Japan are performed with Joboji urushi only.

Hidehira-nuri practicaly a whole region is a National Tresure. Almost exclusively manual techniques (unlike other well know areas), unusual textures and motives, extensive use of locally produced gold leaves.

Kagawa prefecture

Kagawa-nuri is known for kinma and sensei techniques. Both use hairline carving in lacquer but unlike chinkin – carvings are filled with various colours of lacquer, not gold.

Odawara shikki – dominating techniques are kijiro and fuki-urushi – both exposing natural grain of wood.

Kanagawa prefecture

Kamakura-bori. Best known for complex carving techniques covered with lacquer. Also under Chinese influence a lot of carving techniques were adopted and developed along with often thick lacquering. On the crossroads of those two trends kamakura-bori was born – intricate carvings, both on small, netsuke size objects as well as very large – whole buildings, the wood is first carved, and later lacquered, often with techniques very different to other regions, due to the need of preserving the carving aor even highlight it. Use of ink for shading also originates from Kanagawa prefecture.

Kyoto

Kyo-shikki – a source of wabi-sabi aesthetic philosophy and highest quality and durability lacquerware. What sets apart Kyo-shikki is the primer used here, the foundation. In most regions honkataji, honji or makiji is used. In Kyoto traditionally used primer is nuri-kasane – much more laborious, much more expensive and much more durable. For decoration a very wide range of techniques is used from maki-e to raden. A lot of other regions (including Wajima and modern Echizen high end lacquerware) were influenced by Kyo artisans. For me personally – a reference point for quality.

Miyagi prefecture

Naruko-shikki. Most notable techniques are fuki and kijiro urushi, as well as ryumon – dragon pattern, a marbled patterning with use of ink. Base is wood, usually thicker (and stronger) than in other regions.

Nagano prefecture

Kiso-nuri. Around city of Shiojiri. Abundance of great quality wood (Japanese cypress and thujopsis) were importan factors for development of techniques used in Kiso-nuri. Kiso shunkei – local version of fuki-urushi, kiso tsuishu with its texture created by tapping a pad soaked in thick lacquer on the surface and nuriwakero-ironuri – colourful geometric forms.

Niigata prefecture

Niigata-shikki – vast range of techniques used in Niigata can be a subject of studies for any urushi urushi enthusiast for many years. hana-nuri, ishime-nuri, nishiki-nuri, isokusa-nuri and take-nuri among traditional techniques, with many more developed later kinma-nuri, seido-nuri, aokai-nuri, roiro-nuri and shitan-nuri or most recent yuhi-nuri.

Murakami Kibori Tsuishu is another area (along Kamabura-bori) where carving and lacquer go together. Based on chinese tekko (first thick layers of lacquer than carving) Murakami kibori tsuishu is carving directly in wood and then covering it with lacquer with great attention to preserving the the carving – viscosity of lacquer and skills of workers are key to this. Another characteristic of it’s products is matte surface which gets the lustre only with use.

Okinawa

Ryukyu-shikki Okinawa island climate and Chinese influence were important factors of development of urushi in this region. High quality, wide range of techniques, with some of them typical to this region (tsuikin, tsuishu).

Toyama prefecture

Takaoka-shikki known for very wide range of techniques and styles, with various raden and aogai in the first place. Mother-of-pearl and abalone inlays in urushi originates from China and you can see it best on some Takaoka-shikki products. Both thin 0.1mm nacre pieces as well as thicker more typical for other japanese regions 0.3 are used. Cracked raden, large inlays with engravings are direct implementation of much older Chinese techniques. Kawari-nuri with use of glass, pebbles, even plastic and opal was developed here too.

Wakayama prefecture

Kishu-nuri or Kuroe-nuri – a source of simple, durable urushi lacquerware, birthplace of negoro-nuri – a blcka/vermillion pattern created originally by long, intense use and wearing off the top layers, but later recreated on purpose. In recent times also a mass producer of plastic “urushi-like” utensils.

Yamaguchi prefecture

Ouchi-nuri. Apart from bowls and trays decorated with gold leaf cut into diamond shapes (Ouchin clan crest) regione is best known for its urushi lacquered dolls – a very popular souvenir. Almond shape, round faces, richly decorated and always in pairs. It’s another influence of Kyoto artists – first dolls were made by doll makers moved here from Kyoto by Hiroyo Ouchi